Preserving the Past, Building the Future

The Cotton Club

2nd story of Cotton Club

Like other towns and cities in the Deep South, Gainesville, the county seat of Alachua County, was strictly segregated. Churches, schools, social clubs, hotels, stores, restaurants, movie theatres, and other public places were segregated by custom and law. Although African Americans had served on the county commission and the city council and held elected office during the period of Reconstruction, by the 1940s and 1950s, the governments, civic and business leaders of the city were all white men and women. Nevertheless, there was a vibrant and active Black community, the largest concentration located in the northwest section of the town. Two movie theatres, the Lincoln and the Rose, drew film fans and there were a number of social halls and nightclubs such as Wabash Hall (which is still standing) and Sarah’s club which featured such well-known entertainers as Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington and others who regularly toured a circuit of clubs that catered to an African Americans throughout the country. A popular booking might draw from as far away as Jacksonville, Ocala, or Palatka. Most of these entertainers stayed at the Dunbar Hotel, located in what is now the Pleasant Street Historic District.

While the largest population of black families and businesses surrounding Seminary Avenue (NW 5th Ave), African Americans had also lived and worked in Porters Quarters and Springhill since the nineteenth century, areas located south of the downtown area in a largely industrial part of Gainesville. In 1938 a study “Negro Life in Gainesville” described the Springhill neighborhood as “semi-rural”. It stretched south and east of the old Gainesville depot “extending in a scattered settlement towards the woods” and was “lacking in city improvements”. It was in this area that the cotton club was located.

As the home of the University of Florida, Gainesville boomed after World War II as veterans enrolled by the thousands under the GI Bill. Many were from other parts of the country or had traveled widely during their service careers, and they were attuned to the popular music played by the African American bands and vocalists that filled the radio airwaves…jazz, bebop, the blues, and rhythm and blues. The music that had roots in African drumming and dancing, Black gospel music, work songs, and the mournful Blues was attracting white enthusiasts as well as its traditional base from the Black community. The Chitlin’ Circuit was established as a vehicle to book entertainers throughout the country, and in the 1940s, radio stations created new audiences when they began to play records of Black singers and musicians.

There are six of the nine buildings originally located on the site still remaining. The hall, grocery store, and four small houses adjacent to the Mount Olive A.M.E. Church portray a period in African American history that is disappearing without being recorded. During the period of segregation, most newspapers carried very little, if any, news about blacks. The Gainesville Sun was no exception. Only the obituaries were included and these were usually of the more affluent blacks. The lives of poor blacks, the ones that toiled in the factories, struggling to make ends meet, were not recorded. This site showed the close proximity, in which people worked, shopped, played, and worshipped. The buildings with their weathered siding and hurricane-damaged roofs in this small community are easily overlooked, however, that would be a mistake as they provide a unique view into the life of African Americans during the period of segregation. They tell a story of strength, perseverance, adaptability, not unlike the people who utilized them.

The Perryman Movie Theatre

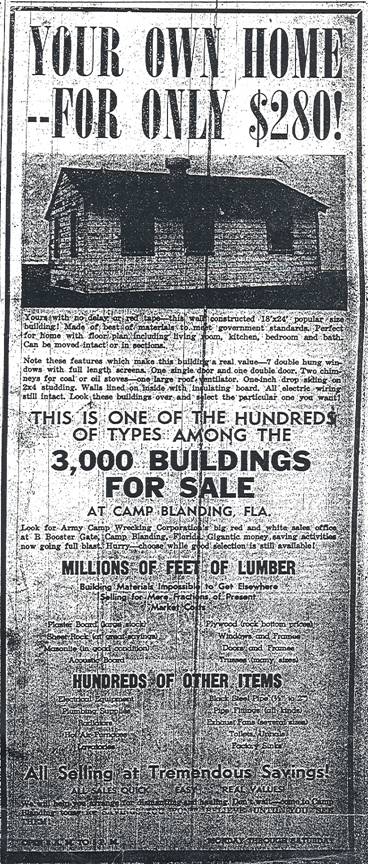

The wood-frame structure that became the cotton club was built between 1940 and 1941 as a Post Exchange (PX) at Camp Blanding in Stark, Florida, north of Gainesville. Camp Blanding was activated as an induction center for the US army in the September of 1940 on the land owned by the Florida National Guard. The army built hundreds of wood-frame buildings at this time to accommodate the thousands of trainees and inductees. When Camp Blanding closed in the March of 1946 at the end of World War II, the building was one of 3000 that was put up on sale.

William and Eunice Perryman, who owned a grocery store on what was then called the East Depot Avenue or Cecil Avenue (now SE 7th Ave), Put in a Successful bid for one of the PX buildings and had the structure moved, in several pieces, down the Waldo Road to a lot near their store. Their granddaughter Betty Themes, in a phone interview, recalled that it was a large undertaking to move the building, which the Perrymans soon opened as the Perry Theater. In 1946 the only other choices of film entertainment for the blacks were the Lincoln Theater and the Rose Theater at the north side of the town, on West Seminary Street (NW 5th Avenue). The Perrymans, planning to attract moviegoers on the south side of town, installed a cement floor projection room in the north end of the building and one of Perryman’s sons William Alexander Perryman, ran the projector. Wooden theater seats were installed and posters in front advertised the coming attractions. Westerns starring Johnny Mack Brown and Hopalong Cassidy were popular with the local children, according to the recollections of Jasper Stephenson, who grew up in the Springhill neighborhood.

According to Gainesville City Directories, the Perry Theater was in operation during 1948 and 1949. Mrs.Temes indicated that the theater, which was only open from Thursday to Saturday, did not produce the expected revenue and closed after a few years. Shortly after it closed as a theater, it opened as the Cotton Club, listed in the 1951-1952 city directory as a place where beverages were sold.

The Cotton Club The Perry

Two interviews with Charles McKnight, the son of Sarah and Charles McKnight, who ran the Cotton Club, revealed that a number of African American entertainers who went on to national fame appeared at the Cotton Club. Among them were James Brown, B.B. King, and Brook Benton. Mr. McKnight recalls James Brown singing his future hit “Please, Please, Please” on the Cotton Club stage. The Cotton Club of Gainesville (named for its famous namesake of Harlem) was part of a circuit of nightclubs and ballrooms that booked Black singers and musicians which also included the Club Bali, a popular spot in Ocala that is no longer standing. Sarah McKnight, who was a musician and also operated a club on Seminary Avenue, formed an alliance with the owner of the Club Bali so that the musicians that played one venue usually played both. Mr. McKnight said that patrons paid a cover charge but could buy beverages but not liquor, as Alachua County was a dry County at that time. Patrons could also order food, prepared in a kitchen located in the northwest corner of the building. There was an open counter with a canopy over it in this corner of the club. Bathrooms were located in the northeast corner of the building. Wooden tables covered with tablecloths were set up on either side of the room, leaving the center open for dancing. There was a stage across the south end of the large open room, about four feet high, providing a good view of the entertainers. Mr. McKnight revealed that his mother had plans to build a balcony around the large open room, like that at the Cub Bali, to accommodate the large crowds that the Cotton Club was drawing. Mr. Stephenson also recalled the heyday of the Cotton Club, where dance bands drew large crowds from as far away as Ocala, Palatka, and Jacksonville. In a newspaper interview, he said that the cotton club was also popular with the students and faculty of the University of Florida, which conflicted with the segregation rules of that era. This led he believed to the city denying renewal of the club’s license, which brought its “lively run” to a close. Charles McKnight confirmed this recalling that the club was particularly popular with the ever-influential UF football players and that there was no friction among those that attended the club.

The Gainesville city directories fail to list the Cotton Club between 1953 and 1959 when the building at this address was listed as the Blue Note, described as a Ballroom. The Blue Note, which had a jukebox and sold beer never attained the popularity of the Cotton Club. A very faded Blue Note sign can still be seen on the front façade. The building was purchased in the late 1950s by Kenneth Gibbs and was used as a warehouse for the Babcock Furniture Company until 1970.

The Mt. Olive A.M.E. Church has purchased the building and surrounding property and proposes to restore the building for use as a community center for the Springhill neighborhood.